Lecture: Section 15.8 Triple Integrals in Spherical Coordinates

In the previous section, we simplified triple integrals over regions with symmetry around an axis (like cylinders) using Cylindrical Coordinates.

However, what if our region is symmetric about a point, like the origin? For example, spheres, cones, or regions bounded by them. For these shapes, we introduce our final and perhaps most powerful 3D coordinate system: Spherical Coordinates.

Part 1: Defining Spherical Coordinates

In the Spherical Coordinate system, we locate a point $P(x,y,z)$ using three numbers: $(\rho, \theta, \phi)$.

It is crucial to understand the restrictions on $\phi$. While $\theta$ spins all the way around the $z$-axis ($0$ to $2\pi$), $\phi$ only nods down from the North Pole ($z$-axis) to the South Pole (negative $z$-axis). It never exceeds $\pi$.

Move the sliders to see how $\rho$, $\theta$, and $\phi$ can identify any point.

Relationship to Rectangular Coordinates

Visualizing the right triangle formed by $\rho$, $r$, and $z$.

By using right-triangle trigonometry, we can derive the conversion formulas. If we look at the triangle formed by $\rho$ and the $z$-axis, we see that $z = \rho \cos(\phi)$ and the horizontal distance to the $z$-axis is $r = \rho \sin(\phi)$.

Substituting $r = \rho \sin(\phi)$ into our standard polar formulas ($x=r\cos\theta, y=r\sin\theta$) gives us:

$$ x = \rho \sin(\phi) \cos(\theta) $$

$$ y = \rho \sin(\phi) \sin(\theta) $$

$$ z = \rho \cos(\phi) $$

And for the distance squared:

$$ \rho^2 = x^2 + y^2 + z^2 $$

Visualizing the Coordinate Surfaces

Before we move to integration, it is vital to understand the "grid lines" of this new system. In rectangular coordinates, setting variables to constants gives planes ($x=c, y=c, z=c$). In spherical coordinates, we get three very different fundamental shapes.

Coordinate Surface #1

Describe the surface defined by the equation $\rho = c$ (where $c$ is a constant).

Answer: A Sphere.

If we fix the distance from the origin to be constant (e.g., $\rho = 2$), but let the angles $\theta$ and $\phi$ vary, we trace out a sphere centered at the origin.

Coordinate Surface #2

Describe the surface defined by the equation $\theta = c$ (where $c$ is a constant, e.g., $\theta = \pi/4$).

Answer: A Vertical Half-Plane.

This is the same as in cylindrical coordinates. If we fix the angle $\theta$, we are constrained to a vertical "door" swinging out from the $z$-axis.

Coordinate Surface #3

Describe the surface defined by the equation $\phi = c$ (where $c$ is a constant, e.g., $\phi = \pi/4$).

Answer: A Cone.

If we fix the angle off the vertical axis, we trace out a cone. (Specifically, the top half of a cone if $0 < c < \pi/2$).

Part 2: The Spherical Volume Element $dV$

Just as we needed a conversion factor for polar ($r$) and cylindrical ($r$) coordinates, we need one for spherical coordinates. This is the most complex one we will learn.

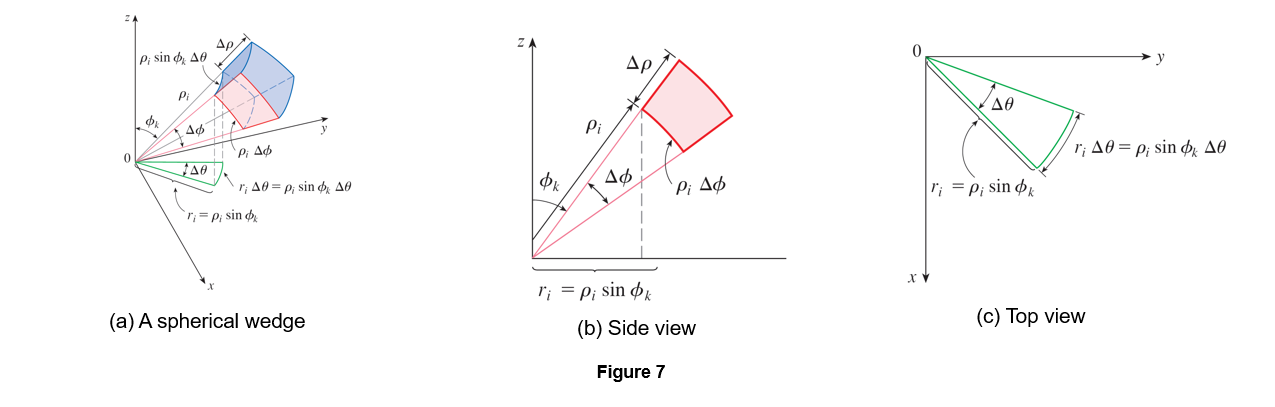

Consider a small "spherical wedge" defined by small changes $\Delta \rho$, $\Delta \theta$, and $\Delta \phi$. We approximate this wedge as a rectangular box.

Left: Interactive wedge. Right: Diagram showing side lengths. Note that side lengths include $\rho$ and $\sin\phi$.

The dimensions of this "box" are:

- Length 1: $\Delta \rho$ (change in radius).

- Length 2: $\rho \, \Delta \phi$ (arc length of the vertical circle).

- Length 3: $(\rho \sin\phi) \, \Delta \theta$ (arc length of the horizontal circle at radius $r = \rho\sin\phi$).

Multiplying these three dimensions gives us the volume approximation:

$$ \Delta V \approx (\Delta \rho) \cdot (\rho \Delta \phi) \cdot (\rho \sin\phi \Delta \theta) = \rho^2 \sin\phi \, \Delta \rho \, \Delta \theta \, \Delta \phi $$

The Golden Rule of Spherical Integration

The volume element in spherical coordinates is:

$$ dV = \rho^2 \sin(\phi) \, d\rho \, d\theta \, d\phi $$

You must memorize the factor $\rho^2 \sin(\phi)$. Without it, your integral will be incorrect.

Part 3: Evaluating Integrals in Spherical Coordinates

We typically integrate in the order $d\rho \, d\phi \, d\theta$, though the order of $\phi$ and $\theta$ can be swapped since their bounds are usually constants.

Example 1: Evaluating an Integral over a Ball

Evaluate $\iiint_B e^{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}} \, dV$, where $B$ is the unit ball $x^2+y^2+z^2 \le 1$.

Solution:

Trying to solve this in rectangular coordinates is a nightmare. The bounds would involve square roots, and the integrand is difficult. In spherical coordinates, this is elegant.

1. Describe the Region $B$: The unit ball is the collection of all points with distance $\rho \le 1$. It covers all angles.

$$ B = \{ (\rho, \theta, \phi) \mid 0 \le \rho \le 1, \, 0 \le \theta \le 2\pi, \, 0 \le \phi \le \pi \} $$

2. Convert the Integrand: Since $x^2+y^2+z^2 = \rho^2$, the integrand becomes:

$$ e^{(\rho^2)^{3/2}} = e^{\rho^3} $$

3. Set up and Evaluate: Don't forget the $\rho^2 \sin\phi$ from $dV$!

$$ I = \int_0^{\pi} \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^1 e^{\rho^3} \cdot (\rho^2 \sin\phi) \, d\rho \, d\theta \, d\phi $$

We can split this integral because the limits are constant and the integrand is a product of functions of single variables:

$$ I = \left( \int_0^{\pi} \sin\phi \, d\phi \right) \left( \int_0^{2\pi} d\theta \right) \left( \int_0^1 \rho^2 e^{\rho^3} \, d\rho \right) $$

Calculate each part:

- $\int_0^{\pi} \sin\phi \, d\phi = [-\cos\phi]_0^{\pi} = -(-1) - (-1) = 2$.

- $\int_0^{2\pi} d\theta = 2\pi$.

- For $\int \rho^2 e^{\rho^3} d\rho$, let $u = \rho^3, du = 3\rho^2 d\rho$. Then $\int \rho^2 e^{\rho^3} d\rho = \frac{1}{3}e^{\rho^3}$.

- $\int_0^1 \rho^2 e^{\rho^3} \, d\rho = [\frac{1}{3}e^{\rho^3}]_0^1 = \frac{1}{3}(e - 1)$.

Final Answer: $I = (2)(2\pi)(\frac{1}{3}(e-1)) = \frac{4\pi}{3}(e-1)$.

Example 2: Volume of an "Ice Cream Cone"

Find the volume of the solid $E$ that lies above the cone $z = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ and below the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2 = z$.

The solid bounded by a cone below and a shifted sphere above.

Solution:

First, let's convert the equations to spherical coordinates.

Step-by-Step: Converting the Cone

Students often struggle with why $z = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ becomes $\phi = \pi/4$. Let's convert everything to spherical variables:

- $z = \rho \cos\phi$

- $\sqrt{x^2+y^2} = \sqrt{(\rho\sin\phi\cos\theta)^2 + (\rho\sin\phi\sin\theta)^2} = \sqrt{\rho^2\sin^2\phi(\cos^2\theta+\sin^2\theta)} = \rho\sin\phi$

Set them equal: $$ \rho \cos\phi = \rho \sin\phi $$

Assuming $\rho \neq 0$, divide by $\rho$: $$ \cos\phi = \sin\phi \implies 1 = \tan\phi \implies \phi = \pi/4 $$

Why is it a cone? Notice that $\rho$ and $\theta$ completely cancelled out. This means $\rho$ and $\theta$ can be anything. The only restriction is that the angle $\phi$ must be $\pi/4$. This traces out a cone!

The Sphere: $x^2+y^2+z^2 = z$ becomes $\rho^2 = \rho \cos\phi$. Dividing by $\rho$, we get $\rho = \cos\phi$.

The Limits:

- $\theta$: Full rotation, $0 \le \theta \le 2\pi$.

- $\phi$: From the $z$-axis ($0$) down to the cone ($\pi/4$). So $0 \le \phi \le \pi/4$.

- $\rho$: From the origin ($0$) out to the sphere boundary ($\cos\phi$). So $0 \le \rho \le \cos\phi$.

The Integral:

$$ V = \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{\pi/4} \int_0^{\cos\phi} 1 \cdot (\rho^2 \sin\phi) \, d\rho \, d\phi \, d\theta $$

Inner ($\rho$): $\int_0^{\cos\phi} \rho^2 \sin\phi \, d\rho = \sin\phi [\frac{\rho^3}{3}]_0^{\cos\phi} = \frac{1}{3} \cos^3\phi \sin\phi$.

Middle ($\phi$): $\int_0^{\pi/4} \frac{1}{3} \cos^3\phi \sin\phi \, d\phi$. Let $u = \cos\phi$, $du = -\sin\phi \, d\phi$.

Limits: $\phi=0 \to u=1$, $\phi=\pi/4 \to u=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$.

$$ \int \dots = -\frac{1}{3} \int_1^{\sqrt{2}/2} u^3 \, du = \frac{1}{3} \int_{\sqrt{2}/2}^1 u^3 \, du = \frac{1}{3} [\frac{u^4}{4}]_{\sqrt{2}/2}^1 $$

$$ = \frac{1}{12} (1^4 - (\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2})^4) = \frac{1}{12} (1 - \frac{4}{16}) = \frac{1}{12} (1 - \frac{1}{4}) = \frac{1}{12}(\frac{3}{4}) = \frac{1}{16} $$

Outer ($\theta$): $\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{1}{16} \, d\theta = \frac{2\pi}{16} = \frac{\pi}{8}$.

Check Your Understanding

Set up the triple integral for the volume of the solid lying between the spheres $\rho = 1$ and $\rho = 2$ and inside the cone $\phi = \pi/3$.

Solution:

1. Bounds:

- $\rho$ goes from the inner sphere to the outer sphere: $1 \le \rho \le 2$.

- $\phi$ goes from the $z$-axis to the cone edge: $0 \le \phi \le \pi/3$.

- $\theta$ is a full rotation (implied by "cone"): $0 \le \theta \le 2\pi$.

2. Integral:

$$ V = \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{\pi/3} \int_1^2 \rho^2 \sin\phi \, d\rho \, d\phi \, d\theta $$

Part 4: Summary and Learning Objectives

Spherical coordinates are the natural choice for problems involving spheres, cones, and symmetry about a point. The trade-off for this power is a more complex volume element.

Learning Objectives

After this lecture, you should be able to:

- Define points using $(\rho, \theta, \phi)$ and understand the restrictions on $\phi$.

- Convert between rectangular and spherical coordinates.

- Draw the spherical wedge to justify why $dV = \rho^2 \sin\phi \, d\rho \, d\theta \, d\phi$.

- Set up and evaluate triple integrals for regions bounded by spheres and cones.

Final Check for Understanding

Try these additional problems to ensure you have mastered the material.

Final Check #1 (Evaluation)

Evaluate $\iiint_E z \, dV$, where $E$ is the upper hemisphere of radius 2 (defined by $x^2+y^2+z^2 \le 4$ and $z \ge 0$).

Solution:

1. Bounds:

- $\rho$: From the center to the edge, $0 \le \rho \le 2$.

- $\phi$: From the "North Pole" ($z$-axis) to the "Equator" ($xy$-plane), $0 \le \phi \le \pi/2$.

- $\theta$: Full rotation, $0 \le \theta \le 2\pi$.

2. Convert Integrand: $z = \rho \cos\phi$.

3. Integral:

$$ I = \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{\pi/2} \int_0^2 (\rho \cos\phi) \cdot (\rho^2 \sin\phi) \, d\rho \, d\phi \, d\theta $$

$$ I = \left(\int_0^{2\pi} d\theta \right) \left( \int_0^2 \rho^3 d\rho \right) \left( \int_0^{\pi/2} \cos\phi \sin\phi \, d\phi \right) $$

Evaluate:

- $\theta$: $2\pi$.

- $\rho$: $[\frac{\rho^4}{4}]_0^2 = \frac{16}{4} = 4$.

- $\phi$: Let $u = \sin\phi$. $\int_0^1 u \, du = 1/2$.

Result: $I = (2\pi)(4)(1/2) = 4\pi$.

Final Check #2 (Volume Setup)

Set up the integral for the volume of the solid region bounded between the spheres $\rho = 2$ and $\rho = 4$, and inside the cone $\phi = \pi/6$.

Solution:

1. Bounds:

- $\rho$: Bounded between the two spheres, $2 \le \rho \le 4$.

- $\phi$: From the vertical axis to the cone, $0 \le \phi \le \pi/6$.

- $\theta$: Full rotation, $0 \le \theta \le 2\pi$.

2. Integral: We are finding volume, so the function is 1.

$$ V = \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{\pi/6} \int_2^4 1 \cdot (\rho^2 \sin\phi) \, d\rho \, d\phi \, d\theta $$