Lecture: Section 15.6 Triple Integrals

Welcome! We have seen how single integrals $\int_a^b f(x) \,dx$ allow us to find the area under a 2D curve, and double integrals $\iint_D f(x,y) \,dA$ allow us to find the volume under a 3D surface.

Today, we move into the third dimension with Triple Integrals. It's tempting to think this will compute "hypervolume" in 4D, and mathematically it does. But for us, it has a much more physical and intuitive meaning.

What is a Triple Integral?

A triple integral $\iiint_E f(x,y,z) \,dV$ is the integral of a function $f(x,y,z)$ over a 3D solid region $E$.

We find it by chopping the region $E$ into tiny boxes, each with volume $\Delta V = \Delta x \Delta y \Delta z$. We take the value of $f$ at a point in each box, multiply it by $\Delta V$, and add them all up:

$$ \iiint_E f(x,y,z) \,dV = \lim_{\Delta V \to 0} \sum f(x_i, y_j, z_k) \Delta V $$

The two most important interpretations:

- If $f(x,y,z) = 1$, then the integral is the Volume of the solid $E$.

$$ V(E) = \iiint_E 1 \,dV $$ - If $f(x,y,z) = \rho(x,y,z)$ (a density function), then the integral is the Mass of the solid $E$.

$$ m(E) = \iiint_E \rho(x,y,z) \,dV $$

Part 1: Triple Integrals over Rectangular Boxes 📦

Just like with double integrals, we start with the simplest possible region: a rectangular box.

A box $B$ can be defined as $B = [a, b] \times [c, d] \times [r, s]$, which means $a \le x \le b$, $c \le y \le d$, and $r \le z \le s$.

Fubini's Theorem (for Triple Integrals)

If $f$ is continuous on the rectangular box $B$, then we can compute the triple integral as an iterated integral. The order of integration does not matter.

$$ \iiint_B f(x,y,z) \,dV = \int_r^s \int_c^d \int_a^b f(x,y,z) \,dx \,dy \,dz $$

We can use any of the $3! = 6$ possible orders of integration ($dx\,dy\,dz$, $dz\,dx\,dy$, etc.).

Example 1: Evaluating over a Box

Evaluate $\iiint_B xyz^2 \,dV$ if $B = [1, 2] \times [-1, 1] \times [0, 3]$.

Solution:

Let's choose the order $dx\,dy\,dz$. This breaks the "all bounds are zero" pattern early!

$$ \int_0^3 \int_{-1}^1 \int_1^2 xyz^2 \,dx \,dy \,dz $$

Inner (with respect to $x$):

$$ \int_1^2 xyz^2 \,dx = yz^2 \left[ \frac{1}{2}x^2 \right]_1^2 = yz^2 \left( \frac{4}{2} - \frac{1}{2} \right) = \frac{3}{2} yz^2 $$

Middle (with respect to $y$):

$$ \int_{-1}^1 \frac{3}{2} yz^2 \,dy = \frac{3}{2}z^2 \left[ \frac{1}{2}y^2 \right]_{-1}^1 = \frac{3}{2}z^2 \left( \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{2} \right) = 0 $$

Outer (with respect to $z$):

$$ \int_0^3 0 \,dz = 0 $$

(Note: The integral is zero because the function $f(x,y,z) = xyz^2$ is an odd function with respect to $y$, and we integrated over a symmetric $y$-interval $[-1, 1]$.)

Example 2: Separable Integrals

Evaluate $\iiint_B e^{x+y+z} \,dV$ over the box $B = [0, 1] \times [0, \ln(2)] \times [0, \ln(3)]$.

Solution:

The function can be written as $f(x,y,z) = e^x e^y e^z$. When the function is separable and the limits are constants, we can separate the integral:

$$ \iiint_B e^x e^y e^z \,dV = \left( \int_0^1 e^x \,dx \right) \left( \int_0^{\ln(2)} e^y \,dy \right) \left( \int_0^{\ln(3)} e^z \,dz \right) $$

$$ = \left[ e^x \right]_0^1 \cdot \left[ e^y \right]_0^{\ln(2)} \cdot \left[ e^z \right]_0^{\ln(3)} $$

$$ = (e^1 - e^0) \cdot (e^{\ln(2)} - e^0) \cdot (e^{\ln(3)} - e^0) $$

$$ = (e - 1) \cdot (2 - 1) \cdot (3 - 1) = 2(e - 1) $$

Check Your Understanding #1

Evaluate $\int_0^{\pi} \int_0^1 \int_0^2 z \cos(y) \,dx \,dz \,dy$.

Part 2: Triple Integrals over General Regions 🏔️

This is where things get interesting. Most solids are not simple boxes. We must define our limits of integration using functions.

The strategy is to define the region $E$ by "trapping" one variable between two surfaces (the "floor" and "ceiling") and then projecting the solid onto a 2D plane to create a "shadow" region $D$.

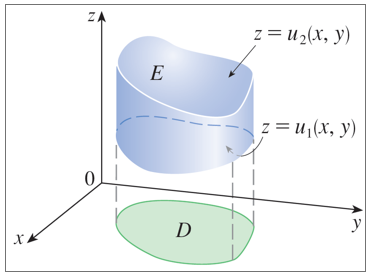

A general $z$-simple region $E$ bounded by a floor $z=u_1(x,y)$ and a ceiling $z=u_2(x,y)$. Its shadow $D$ lies in the $xy$-plane.

The Strategy: Type 1 Regions ($z$-simple)

We say a region $E$ is $z$-simple if it lies between two surfaces $z = u_1(x,y)$ (the floor) and $z = u_2(x,y)$ (the ceiling).

$$ E = \{ (x,y,z) \mid (x,y) \in D, \, u_1(x,y) \le z \le u_2(x,y) \} $$

Here, $D$ is the 2D projection (shadow) of $E$ onto the $xy$-plane.

To evaluate the integral:

$$ \iiint_E f(x,y,z) \,dV = \iint_D \left[ \int_{u_1(x,y)}^{u_2(x,y)} f(x,y,z) \,dz \right] \,dA $$

This breaks the problem down:

- Innermost integral (for $dz$): Integrate from the floor surface to the ceiling surface. The result will only have $x$ and $y$.

- Outer double integral (for $dA$): Integrate the result over the 2D shadow region $D$, just like in sections 15.2 and 15.3.

Example 3: Volume of a Tetrahedron

Find the volume of the solid tetrahedron $E$ bounded by the planes $x + 2y + z = 2$, $x = 0$, $y = 0$, and $z = 0$.

Solution:

Step 1: Find the $z$-limits (floor and ceiling).

First, let's visualize the solid.

The solid tetrahedron $E$ in the first octant.

A ray parallel to the $z$-axis enters at the "floor" $z = 0$. It exits at the "ceiling", which is the slanted plane $x + 2y + z = 2$. We solve this for $z$:

$$ z = 2 - x - 2y $$

So, our $z$-limits are $0 \le z \le 2 - x - 2y$.

Step 2: Set up the Inner Integral.

This gives us the innermost integral. The volume $V$ is the integral over the solid $E$, which we can write as a double integral over the shadow $D$ of an inner $z$-integral:

$$ V = \iiint_E 1 \,dV = \iint_D \left[ \int_0^{2-x-2y} 1 \,dz \right] \,dA $$

Step 3: Find the 2D shadow region $D$ in the $xy$-plane.

The shadow $D$ is the 2D region in the $xy$-plane directly "under" the solid. This is the region where the solid meets the $xy$-plane ($z=0$). We set $z=0$ in the ceiling equation: $0 = 2 - x - 2y$, which gives $x + 2y = 2$.

This line, along with $x=0$ and $y=0$, forms our triangular shadow $D$. We can write $D$ as a Type I 2D region:

Solve for $y$: $y = 1 - x/2$. So, $D = \{ (x,y) \mid 0 \le x \le 2, \, 0 \le y \le 1 - x/2 \}$.

The triangular shadow $D$ in the $xy$-plane, bounded by $x=0$, $y=0$, and $x+2y=2$.

Step 4: Set up and evaluate the full integral.

$$ V = \int_0^2 \int_0^{1-x/2} \left( \int_0^{2-x-2y} 1 \,dz \right) \,dy \,dx $$

Inner ($dz$): $\int_0^{2-x-2y} 1 \,dz = [z]_0^{2-x-2y} = 2 - x - 2y$.

Middle ($dy$): $\int_0^{1-x/2} (2 - x - 2y) \,dy = [2y - xy - y^2]_0^{1-x/2}$

$$ = \left( 2(1-\frac{x}{2}) - x(1-\frac{x}{2}) - (1-\frac{x}{2})^2 \right) - 0 $$

$$ = (2 - x) - (x - \frac{x^2}{2}) - (1 - x + \frac{x^2}{4}) $$

$$ = 2 - x - x + \frac{x^2}{2} - 1 + x - \frac{x^2}{4} = 1 - x + \frac{x^2}{4} $$

Outer ($dx$): $\int_0^2 (1 - x + \frac{x^2}{4}) \,dx = [x - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^3}{12}]_0^2$

$$ = (2 - \frac{4}{2} + \frac{8}{12}) - 0 = (2 - 2 + \frac{2}{3}) = \frac{2}{3} $$

Example 4: Volume Between Two Surfaces

Find the volume of the solid $E$ bounded *between* the two paraboloids $z_1 = x^2+y^2$ (the "floor") and $z_2 = 8 - x^2 - y^2$ (the "ceiling").

Solution:

Step 1 ($z$-limits): The problem gives them to us. The floor is $z_1 = x^2+y^2$. The ceiling is $z_2 = 8 - x^2 - y^2$.

Step 2 (Shadow $D$): To find the $xy$-shadow, we find where the floor and ceiling intersect:

$$ x^2+y^2 = 8 - x^2 - y^2 \implies 2x^2 + 2y^2 = 8 \implies x^2+y^2 = 4 $$

The shadow is a circle in the $xy$-plane of radius 2, centered at the origin.

click off f(x,y) and g(x,y) to see the volume to be computed and see the domain D in the xy plane

Step 3 (Integral): We set up the $...dz \,dy \,dx$ integral. We describe the circular shadow $D$ as a 2D region:

- $-2 \le x \le 2$

- $-\sqrt{4-x^2} \le y \le \sqrt{4-x^2}$

Inner ($dz$): $\int_{x^2+y^2}^{8-x^2-y^2} 1 \,dz = [z]_{x^2+y^2}^{8-x^2-y^2} = (8 - x^2 - y^2) - (x^2+y^2) = 8 - 2x^2 - 2y^2$.

Outer Double Integral:

$$ V = \int_{-2}^2 \int_{-\sqrt{4-x^2}}^{\sqrt{4-x^2}} (8 - 2(x^2+y^2)) \,dy \,dx $$

Converting to Polar Coordinates

This integral is very difficult in rectangular coordinates. We can solve it by converting the *double integral* to polar coordinates.

- The Region $D$: The shadow is a circle $x^2+y^2 \le 4$. In polar, this is simply $0 \le r \le 2$ and $0 \le \theta \le 2\pi$.

- The Integrand: $8 - 2(x^2+y^2)$ becomes $8 - 2r^2$.

- The Differential: $dy \,dx$ becomes $r \,dr \,d\theta$.

Set up the Polar Integral:

$$ V = \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^2 (8 - 2r^2) \cdot r \,dr \,d\theta $$

$$ V = \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^2 (8r - 2r^3) \,dr \,d\theta $$

Inner ($dr$): $\int_0^2 (8r - 2r^3) \,dr = \left[ 4r^2 - \frac{2r^4}{4} \right]_0^2 = \left[ 4r^2 - \frac{r^4}{2} \right]_0^2$

$$ = \left( 4(2)^2 - \frac{(2)^4}{2} \right) - 0 = \left( 16 - \frac{16}{2} \right) = 16 - 8 = 8 $$

Outer ($d\theta$):

$$ V = \int_0^{2\pi} 8 \,d\theta = [8\theta]_0^{2\pi} = 8(2\pi) - 0 = 16\pi $$

Check Your Understanding #2

Set up (but do not evaluate) a triple integral for the mass of the solid $E$ bounded by the parabolic cylinder $z = 1 - y^2$ and the planes $z=0$, $x=0$, $x=1$. The density is given by $\rho(x,y,z) = xz$.

Part 3: A Visual Strategy for Changing Integration Order 🔃

Visualizing the 3D solid is the hardest part of changing the integration order. Instead of a purely algebraic method, let's use a visual, graph-based approach. We will tackle one problem in two different orders to see how the perspective changes.

Example 5: A New Solid - Order 1 ($dz \,dy \,dx$)

Find the volume of the solid $E$ bounded by the surfaces $z=y+1$, $z=x^2+1$, and $y=1$.

Solution (a): Order $dz \,dy \,dx$

Let's start by visualizing the solid. The boundaries are two "troughs" ($z=y+1$ and $z=x^2+1$) cut by the vertical plane $y=1$.

The solid $E$ bounded by $z=y+1$ (red), $z=x^2+1$ (blue), and $y=1$ (green).

We want to set up $V = \iiint_E 1 \,dz \,dy \,dx$. This means our shadow $D$ is in the $xy$-plane. Let's use this view to find the bounds:

Visualizing the order dzdydx, we will go from the bottom surface z = x^2+1 to the top surface z = y+1. the middle integral is y = x^2 to y = 1 and the outer integral is -1 to 1

1. Inner ($z$) bounds: A ray parallel to the $z$-axis (the "Ray") enters the solid at the "floor" $z = x^2+1$ and exits at the "ceiling" $z=y+1$. So, $x^2+1 \le z \le y+1$.

2. Shadow ($D_{xy}$) bounds: The shadow in the $xy$-plane is the 2D region where the solid exists. It's bounded by the plane $y=1$ and the intersection of the two surfaces. Let's find the intersection: $y+1 = x^2+1 \implies y = x^2$. So the shadow is bounded by the line $y=1$ and the parabola $y=x^2$.

For $...dy \,dx$, we have outer $x$-bounds from $-1$ to $1$, and inner $y$-bounds from $y=x^2$ to $y=1$.

3. Set up and Integrate:

$$ V = \int_{-1}^1 \int_{x^2}^1 \int_{x^2+1}^{y+1} 1 \,dz \,dy \,dx $$

Inner ($dz$): $\int_{x^2+1}^{y+1} 1 \,dz = [z]_{x^2+1}^{y+1} = (y+1) - (x^2+1) = y - x^2$.

Middle ($dy$): $\int_{x^2}^1 (y - x^2) \,dy = \left[ \frac{1}{2}y^2 - x^2y \right]_{x^2}^1$

$$ = \left( \frac{1}{2}(1)^2 - x^2(1) \right) - \left( \frac{1}{2}(x^2)^2 - x^2(x^2) \right) = \left(\frac{1}{2} - x^2\right) - \left(\frac{1}{2}x^4 - x^4\right) = \frac{1}{2} - x^2 + \frac{1}{2}x^4 $$

Outer ($dx$): $\int_{-1}^1 \left(\frac{1}{2} - x^2 + \frac{1}{2}x^4\right) \,dx$. This is an even function, so we can simplify:

$$ = 2 \int_0^1 \left(\frac{1}{2} - x^2 + \frac{1}{2}x^4\right) \,dx = 2 \left[ \frac{1}{2}x - \frac{1}{3}x^3 + \frac{1}{10}x^5 \right]_0^1 $$

$$ = 2 \left( \left(\frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{10}\right) - 0 \right) = 2 \left( \frac{15 - 10 + 3}{30} \right) = 2 \left( \frac{8}{30} \right) = \frac{16}{30} = \frac{8}{15} $$

Solution (b): Same Solid, New Order ($dx \,dz \,dy$)

Now, what if we want to change the order to $dx \,dz \,dy$? This means our shadow $D$ is on the $yz$-plane.

1. Inner ($x$) bounds: First, solve any surface involving $x$ for $x$. We have $z = x^2+1 \implies x^2 = z-1 \implies x = \pm\sqrt{z-1}$. This also tells us we must have $z \ge 1$.

A ray parallel to the $x$-axis ("piercing the solid") enters at the "floor" $x = -\sqrt{z-1}$ and exits at the "ceiling" $x = \sqrt{z-1}$. So, $-\sqrt{z-1} \le x \le \sqrt{z-1}$.

2. Shadow ($D_{yz}$) bounds: Now we find the shadow in the $yz$-plane. We are bounded by $y=1$ (a line) and $z=y+1$ (a line). What about $z=x^2+1$? Since $x$ is "crushed" onto this plane, its smallest value is $x=0$. This occurs on the $yz$-plane itself. The surface $z=x^2+1$ starts at $z=1$ (when $x=0$).

So, our shadow is bounded by the three lines: $y=1$, $z=y+1$, and $z=1$.

The $yz$-shadow (in purple) is bounded by $y=1$, $z=y+1$, and $z=1$.

For $...dz \,dy$, our outer $y$-bounds are $0 \le y \le 1$. Our inner $z$-bounds are from the floor $z=1$ up to the ceiling $z=y+1$.

3. Set up and Integrate:

$$ V = \int_0^1 \int_1^{y+1} \int_{-\sqrt{z-1}}^{\sqrt{z-1}} 1 \,dx \,dz \,dy $$

Inner ($dx$): $\int_{-\sqrt{z-1}}^{\sqrt{z-1}} 1 \,dx = [x]_{-\sqrt{z-1}}^{\sqrt{z-1}} = \sqrt{z-1} - (-\sqrt{z-1}) = 2\sqrt{z-1}$.

Middle ($dz$): $\int_1^{y+1} 2(z-1)^{1/2} \,dz = 2 \left[ \frac{2}{3}(z-1)^{3/2} \right]_1^{y+1}$

$$ = \frac{4}{3} \left[ ((y+1)-1)^{3/2} - (1-1)^{3/2} \right] = \frac{4}{3} [y^{3/2} - 0] = \frac{4}{3}y^{3/2} $$

Outer ($dy$): $\int_0^1 \frac{4}{3}y^{3/2} \,dy = \frac{4}{3} \left[ \frac{2}{5}y^{5/2} \right]_0^1 = \frac{8}{15}(1 - 0) = \frac{8}{15}$.

Both methods give the same volume, $V = 8/15$, which confirms our bounds are correct!

Example 6: Evaluating an "Impossible" Integral

Evaluate $\int_0^2 \int_0^{4-x^2} \int_0^x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \,dy \,dz \,dx$.

Solution:

Let's try to integrate as written.

Inner ($dy$): $\int_0^x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \,dy = x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z}$.

Middle ($dz$): $\int_0^{4-x^2} x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \,dz$. This requires us to find the antiderivative of $\frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z}$, which is not possible with standard functions . We must change the order.

Our goal is to make $dz$ the *outer* integral, hoping the inner two integrals simplify the $z$-term.

The original bounds are: $0 \le x \le 2$, $0 \le z \le 4-x^2$, and $0 \le y \le x$. Let's visualize this solid.

Visualize the surface bounded by all constraints.

We want the new order $dy\,dx\,dz$. This means our shadow is on the $xz$-plane. Let's look at that shadow $D_{xz}$ and its new $dx\,dz$ order.

The shadow $D_{xz}$ (purple) is bounded by $x=0, z=0$, and $z=4-x^2$.

To change to a $dx \,dz$ order, we solve for $x$: $z=4-x^2 \implies x^2=4-z \implies x = \sqrt{4-z}$ (since $x \ge 0$).

Our new outer $z$-bounds are $0 \le z \le 4$. Our new middle $x$-bounds are $0 \le x \le \sqrt{4-z}$.

The inner $y$-bounds are given by $y=x$ (ceiling) and $y=0$ (floor), so $0 \le y \le x$.

Set up and Integrate:

$$ \int_0^4 \int_0^{\sqrt{4-z}} \int_0^x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \,dy \,dx \,dz $$

Inner ($dy$): $\int_0^x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \,dy = x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z}$.

Middle ($dx$): $\int_0^{\sqrt{4-z}} x \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \,dx = \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \left[ \frac{1}{2}x^2 \right]_0^{\sqrt{4-z}}$

$$ = \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \left( \frac{(\sqrt{4-z})^2}{2} - 0 \right) = \frac{\sin(2z)}{4-z} \left( \frac{4-z}{2} \right) = \frac{1}{2}\sin(2z) $$

Outer ($dz$): $\int_0^4 \frac{1}{2}\sin(2z) \,dz = \left[ -\frac{1}{4}\cos(2z) \right]_0^4 $

$$ = \left(-\frac{1}{4}\cos(8)\right) - \left(-\frac{1}{4}\cos(0)\right) = \frac{1 - \cos(8)}{4} $$

Check Your Understanding #3

Set up the integral $\iiint_E y \,dV$ where $E$ is bounded by $y=0, y=2, x=0, z=0$, and $z=9-x^2$ in two orders: $dz\,dy\,dx$ and $dx\,dy\,dz$.

Part 4: Applications of Triple Integrals 📐

We can use triple integrals to find properties of 3D solids, not just mass and volume.

Formulas for Applications

Let $E$ be a solid region with a continuous density function $\rho(x,y,z)$.

- Volume: $V = \iiint_E 1 \,dV$

- Mass: $m = \iiint_E \rho(x,y,z) \,dV$

- Moments about Coordinate Planes:

- $M_{yz} = \iiint_E x \rho(x,y,z) \,dV$ (Moment about $yz$-plane)

- $M_{xz} = \iiint_E y \rho(x,y,z) \,dV$ (Moment about $xz$-plane)

- $M_{xy} = \iiint_E z \rho(x,y,z) \,dV$ (Moment about $xy$-plane)

- Center of Mass $(\bar{x}, \bar{y}, \bar{z})$: $$ \bar{x} = \frac{M_{yz}}{m}, \quad \bar{y} = \frac{M_{xz}}{m}, \quad \bar{z} = \frac{M_{xy}}{m} $$ (If density is constant, this is called the Centroid.)

- Average Value of a Function $f$: $$ f_{\text{avg}} = \frac{1}{V(E)} \iiint_E f(x,y,z) \,dV $$

Example 7: Average Value

Find the average value of $f(x,y,z) = xyz$ over the box $B = [0, 1] \times [0, 2] \times [0, 3]$.

Solution:

Step 1: Find the Volume $V(B)$.

$V = (1-0) \cdot (2-0) \cdot (3-0) = 6$.

Step 2: Find the integral $\iiint_B f \,dV$.

$$ \iiint_B xyz \,dV = \left( \int_0^1 x \,dx \right) \left( \int_0^2 y \,dy \right) \left( \int_0^3 z \,dz \right) $$

$$ = \left[ \frac{x^2}{2} \right]_0^1 \cdot \left[ \frac{y^2}{2} \right]_0^2 \cdot \left[ \frac{z^2}{2} \right]_0^3 $$

$$ = \left( \frac{1}{2} \right) \cdot \left( \frac{4}{2} \right) \cdot \left( \frac{9}{2} \right) = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 \cdot \frac{9}{2} = \frac{9}{2} $$

Step 3: Calculate the average.

$$ f_{\text{avg}} = \frac{1}{V(B)} \iiint_B f \,dV = \frac{1}{6} \left( \frac{9}{2} \right) = \frac{9}{12} = \frac{3}{4} $$

Example 8: Setting up Center of Mass

Set up the integrals needed to find the center of mass of the tetrahedron from Example 3 ($E$ bounded by $x+2y+z=2$ and the coordinate planes) assuming constant density $\rho(x,y,z) = k$.

Solution:

The limits of integration are the same as in Example 3: $0 \le x \le 2$, $0 \le y \le 1-x/2$, $0 \le z \le 2-x-2y$.

Mass $m = \iiint_E k \,dV = k \iiint_E 1 \,dV = k \cdot V(E)$. From Example 3, $V(E) = 2/3$, so $m = 2k/3$.

We just need to set up the moments:

$$ M_{yz} = \iiint_E x \rho \,dV = \int_0^2 \int_0^{1-x/2} \int_0^{2-x-2y} (x \cdot k) \,dz \,dy \,dx $$

$$ M_{xz} = \iiint_E y \rho \,dV = \int_0^2 \int_0^{1-x/2} \int_0^{2-x-2y} (y \cdot k) \,dz \,dy \,dx $$

$$ M_{xy} = \iiint_E z \rho \,dV = \int_0^2 \int_0^{1-x/2} \int_0^{2-x-2y} (z \cdot k) \,dz \,dy \,dx $$

Then $\bar{x} = M_{yz} / m$, $\bar{y} = M_{xz} / m$, $\bar{z} = M_{xy} / m$. Notice that the constant $k$ will cancel from the numerator and denominator.

Check Your Understanding #4

A solid $E$ has volume $V=10$. Write the integral expression for the average temperature $T_{\text{avg}}$ of the solid if the temperature at any point is given by $T(x,y,z) = e^{-x^2-y^2-z^2}$.

Part 5: Summary and Learning Objectives ✅

Today we extended our concept of integration into 3D space. We learned how to set up and evaluate iterated integrals over 3D regions, both simple boxes and complex general solids.

Learning Objectives

After this lecture, you should be able to:

- Explain the physical meaning of a triple integral (Volume and Mass).

- Set up and compute triple integrals over rectangular boxes.

- Set up and compute triple integrals over general ($z$-simple, $x$-simple, or $y$-simple) regions by finding the correct limits of integration.

- Change the order of integration for a triple integral to solve difficult problems.

- Set up the integrals for Volume, Mass, Center of Mass, and Average Value of a 3D solid.

Final Check for Understanding

Test your knowledge by trying to solve these problems, which cover all parts of the lecture.

Final Check #1 (Computation)

Evaluate $\iiint_E yz \,dV$ where $E$ is the solid region bounded by $z=0$, $z=x$, $y=0$, $y=1$, and $x=4$.

Final Check #2 (Changing Order)

Set up the integral $\iiint_E x \,dV$ where $E$ is the solid tetrahedron with vertices $(0,0,0), (1,0,0), (0,1,0), (0,0,1)$ in two different orders:

(a) $dz\,dy\,dx$

(b) $dy\,dx\,dz$

Final Check #3 (Application Setup)

Set up the integrals needed to find the $\bar{z}$-coordinate of the centroid (constant density) of the solid $E$ bounded by the paraboloid $z = 1 - x^2 - y^2$ and the plane $z=0$.