Lecture 24: Section 16.1 — Vector Fields

Topic 0: What is a Vector Field? (The "Why")

Up to this point, we have studied scalar functions (or scalar fields), which assign a single number to every point. A great example is a temperature map, $T(x,y)$, which gives the temperature (a scalar) at each point $(x,y)$.

Now, we will study functions that assign a full vector (with magnitude and direction) to every point in a domain. This is the mathematical language used to describe almost every major physical force and flow.

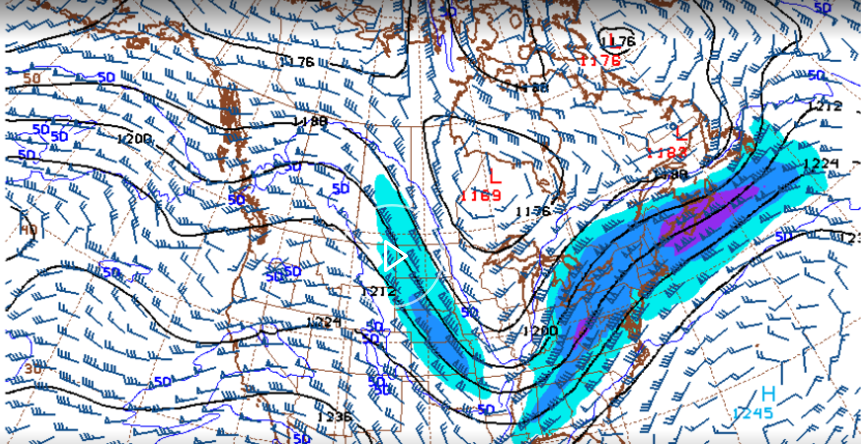

- Wind Map: At every point $(x,y)$ on a map, there is a wind vector representing the wind's speed and direction (e.g., "15 mph to the Northeast"). A map showing all these arrows is a 2D vector field.

- Ocean Currents: At every point $(x,y,z)$ in the ocean, there is a water velocity vector $\vec{v}$. This is a 3D vector field.

- Gravity: Near the Earth, every point $(x,y,z)$ in space has a gravitational force vector $\vec{F}$ pulling objects toward the Earth's center.

- Magnetism: A magnet creates a 3D vector field. Iron filings align themselves with the vectors, allowing us to "see" the field's direction.

Our Goal: Before we can do calculus with these fields (like we will in Section 16.2), we first need to understand what they are, what they look like, and where they come from.

Topic 1: The Rigorous Definition

We formally define a vector field as a function that maps points to vectors.

Definition: Vector Field on $\mathbb{R}^2$

A vector field on $\mathbb{R}^2$ is a function $\vec{F}$ that assigns to each point $(x,y)$ in a 2D domain $D$ a two-dimensional vector $\vec{F}(x,y)$.

We write this using scalar component functions, $P(x,y)$ and $Q(x,y)$: $$\vec{F}(x,y) = \langle P(x,y), Q(x,y) \rangle \quad \text{or} \quad \vec{F}(x,y) = P(x,y)\hat{i} + Q(x,y)\hat{j}$$

Definition: Vector Field on $\mathbb{R}^3$

A vector field on $\mathbb{R}^3$ is a function $\vec{F}$ that assigns to each point $(x,y,z)$ in a 3D domain $E$ a three-dimensional vector $\vec{F}(x,y,z)$.

We write this using component functions $P, Q,$ and $R$: $$\vec{F}(x,y,z) = \langle P(x,y,z), Q(x,y,z), R(x,y,z) \rangle$$

Topic 2: Visualizing Vector Fields in 2D

How can we draw a function that has an infinite number of vectors (one for every point)?

We can't! Instead, we draw a representative sample. We pick a grid of sample points (e.g., all integer coordinates) and draw the vector $\vec{F}$ starting at that point.

Important Note: We often must scale the vectors (draw them shorter than their true magnitude) to prevent them from overlapping into a messy blob. The relative lengths and directions are what matter most in a sketch.

Topic 3: Key Examples of 2D Vector Fields

Let's explore the most common "families" of 2D vector fields.

Example 3A: Sketch the radial field $\vec{F}(x,y) = x\hat{i} + y\hat{j}$

Solution:

Let's find the vector at a few sample points:

- At $(1,0)$, $\vec{F}(1,0) = \langle 1,0 \rangle$ (a vector of length 1 pointing right).

- At $(0,1)$, $\vec{F}(0,1) = \langle 0,1 \rangle$ (a vector of length 1 pointing up).

- At $(2,2)$, $\vec{F}(2,2) = \langle 2,2 \rangle$ (points diagonally up-right).

- At $(-1,0)$, $\vec{F}(-1,0) = \langle -1,0 \rangle$ (points left).

Intuition: At any point $(x,y)$, the vector $\vec{F}(x,y) = \langle x,y \rangle$ is just the position vector of that point. This means all vectors point directly away from the origin.

The magnitude is $|\vec{F}| = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}$, which is the distance from the origin. So, vectors get longer as they get farther out. This looks like an "explosion" field.

In the graph below, "waggle" the slider $s$ to move the point around and get a sense of how the vector (in red) changes dynamically.

Example 3B: Sketch the rotational field $\vec{F}(x,y) = -y\hat{i} + x\hat{j}$

Solution:

Let's plot some vectors on the axes:

- At $(1,0)$ (on the positive x-axis), $\vec{F} = \langle 0,1 \rangle$ (points straight up).

- At $(0,1)$ (on the positive y-axis), $\vec{F} = \langle -1,0 \rangle$ (points straight left).

- At $(-1,0)$ (on the negative x-axis), $\vec{F} = \langle 0,-1 \rangle$ (points straight down).

- At $(0,-1)$ (on the negative y-axis), $\vec{F} = \langle 1,0 \rangle$ (points straight right).

Intuition: This field creates a counter-clockwise rotation or "vortex" around the origin. The magnitude $|\vec{F}| = \sqrt{(-y)^2 + x^2} = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ is the same as the radial field, so vectors get longer as they get farther from the center.

Check: Notice that the vector $\vec{F}=\langle -y,x \rangle$ is always perpendicular to the position vector $\vec{r}=\langle x,y \rangle$. Their dot product is: $$\vec{r} \cdot \vec{F} = \langle x,y \rangle \cdot \langle -y,x \rangle = (x)(-y) + (y)(x) = -xy+xy=0.$$

In the graph below, "waggle" the slider $s$ to see how the rotational vector (in red) is always tangent to the circle.

Topic 4: Vector Fields in 3D

Visualizing 3D vector fields is much harder, as we have 3D vectors at every point in 3D space. We usually rely on computers or by analyzing the field's behavior on specific planes or axes.

Example 4A: Analyze the 3D field $\vec{F}(x,y,z) = \langle y, z, x \rangle$

Solution:

Let's test a few points on the axes:

- On the x-axis, let $(x,y,z) = (2,0,0)$. $\vec{F}(2,0,0) = \langle 0, 0, 2 \rangle$. This is a vector pointing straight up the z-axis.

- On the y-axis, let $(x,y,z) = (0,2,0)$. $\vec{F}(0,2,0) = \langle 2, 0, 0 \rangle$. This is a vector pointing along the x-axis.

- On the z-axis, let $(x,y,z) = (0,0,2)$. $\vec{F}(0,0,2) = \langle 0, 2, 0 \rangle$. This is a vector pointing along the y-axis.

This field has a complex "twisting" or "cycling" behavior. The $x$-component is determined by $y$, the $y$-component by $z$, and the $z$-component by $x$.

In the graph below, waggle the slider $s$ and also rotate the 3D view to see the field action from different perspectives.

Example 4B: Analyze the 3D field $\vec{F}(x,y,z) = \langle y/z, -x/z, z/4 \rangle$

Solution:

This field is not defined on the $xy$-plane (where $z=0$). Let's analyze it on the plane $z=1$:

- On the plane $z=1$, the field becomes $\vec{F}(x,y,1) = \langle y, -x, 1/4 \rangle$.

- If we are on the plane $z=2$, the field is $\vec{F}(x,y,2) = \langle y/2, -x/2, 2/4 \rangle = \langle y/2, -x/2, 1/2 \rangle$.

Intuition: The $\langle y/z, -x/z \rangle$ components create a clockwise rotation around the $z$-axis. The $z/4$ component means the field also points "up" (for $z>0$) with a strength proportional to $z$. This looks like a whirlpool spinning clockwise and moving faster and faster up the $z$-axis.

In the graph below, waggle the slider $s$ and also view the 3D vector field from different perspectives.

Topic 5: Gradient Fields (A Crucial Connection)

Where do vector fields come from? A very important source is from scalar functions (like temperature, altitude, or electric potential).

Recall from Chapter 14: The gradient of a scalar function $f$ is itself a vector field.

Definition: Conservative Vector Field

A vector field $\vec{F}$ is called a conservative vector field if it is the gradient of some scalar function $f$. That is, $\vec{F} = \nabla f$.

Definition: Potential Function

If $\vec{F} = \nabla f$, the scalar function $f$ is called a potential function for $\vec{F}$.

(Analogy: Think of $f$ as the "potential energy" and $\vec{F} = \nabla f$ as the "force" field.)

Example 5A: Find the 2D gradient vector field of $f(x,y) = x^2y - y^3$

Solution:

- Find the partial derivatives:

$f_x = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(x^2y - y^3) = 2xy$

$f_y = \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(x^2y - y^3) = x^2 - 3y^2$

- Assemble the gradient vector:

$\vec{F} = \nabla f = \langle f_x, f_y \rangle = \langle 2xy, x^2 - 3y^2 \rangle$

- Conclusion: The vector field $\vec{F}(x,y) = \langle 2xy, x^2 - 3y^2 \rangle$ is, by definition, a conservative vector field.

Example 5B: Find the 3D gradient vector field of $f(x,y,z) = x \sin(yz)$

Solution:

- Find the partial derivatives:

$f_x = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(x \sin(yz)) = \sin(yz)$

$f_y = \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(x \sin(yz)) = x \cos(yz) \cdot z = xz\cos(yz)$

$f_z = \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(x \sin(yz)) = x \cos(yz) \cdot y = xy\cos(yz)$

- Assemble the gradient vector:

$\nabla f = \langle f_x, f_y, f_z \rangle = \langle \sin(yz), xz\cos(yz), xy\cos(yz) \rangle$

- Conclusion: This 3D vector field is conservative, and $f$ is its potential function.

Check Your Understanding

Problem: Is the rotational field $\vec{F} = \langle -y, x \rangle$ conservative? (In other words, could it come from a gradient?)

This is a subtle question that we will answer fully in Section 16.3. For now, we can use a test for conservative fields (Clairaut's Theorem):

If $\vec{F} = \langle P, Q \rangle = \nabla f = \langle f_x, f_y \rangle$, then we must have $P_y = f_{xy}$ and $Q_x = f_{yx}$. By Clairaut's Theorem, $f_{xy}$ must equal $f_{yx}$, so we must have $P_y = Q_x$.

- Identify P and Q: $P = -y$ and $Q = x$.

- Find partials:

$P_y = \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(-y) = -1$

$Q_x = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(x) = 1$

- Compare: $P_y \neq Q_x$ (since $-1 \neq 1$).

- Conclusion: The test fails. This field is not conservative. There is no potential function $f$ that could create this field.

Topic 6: The Geometry of Gradient Fields

A key property of gradient fields, which we learned in Chapter 14, is their geometric relationship to the level curves (in 2D) or level surfaces (in 3D) of their potential function $f$.

This relationship is the visual signature of a conservative field. If a vector field's arrows are not perpendicular to its (implied) level curves, it cannot be a conservative field.

The Gradient and Level Curves/Surfaces

The gradient vector $\nabla f$ at a point $p$ is always orthogonal (perpendicular) to the level curve (or level surface) $f=k$ that passes through that point $p$.

Intuition (The Mountain Map):

- Think of $f(x,y)$ as an altitude map of a mountain.

- The level curves ($f(x,y)=k$) are the "contour lines" where the altitude is constant.

- The gradient field ($\nabla f$) points in the direction of steepest ascent (the fastest way up the hill).

- To go straight up the hill, you must walk perpendicular to the contour line.

Example 6A: Visualizing $\nabla f$ and Level Curves (2D)

Problem: Show this property for the potential function $f(x,y) = x^2 + y^2$.

Solution:

- Level Curves: $f(x,y)=k$ gives $x^2+y^2=k$. These are circles centered at the origin.

- Gradient Field: $\vec{F} = \nabla f = \langle f_x, f_y \rangle = \langle 2x, 2y \rangle$.

- Visualization: The gradient field $\langle 2x, 2y \rangle$ is a radial field. All vectors point straight out from the origin.

A vector pointing straight out from the origin is always perpendicular to a circle centered at the origin.

Thus, the gradient field is perfectly orthogonal to the level curves.

Example 6B: Visualizing $\nabla f$ and Level Surfaces (3D)

Problem: Show this property for the potential function $f(x,y,z) = x^2 + y^2 + z^2$.

Solution:

- Level Surfaces: $f(x,y,z)=k$ gives $x^2+y^2+z^2=k$. These are spheres centered at the origin.

- Gradient Field: $\vec{F} = \nabla f = \langle f_x, f_y, f_z \rangle = \langle 2x, 2y, 2z \rangle$.

- Visualization: The gradient field $\langle 2x, 2y, 2z \rangle$ is a 3D radial field. All vectors point straight out from the origin.

A vector pointing straight out from the origin is always perpendicular to the surface of a sphere centered at the origin.

Thus, the gradient field is perfectly orthogonal to the level surfaces.

In the graph below, waggle $s$ to see the direction of the vector field, and waggle $b$ to see the level surfaces.

Topic 7: 3D Example - Gravitational Fields

We can describe gravity perfectly using vector fields. By Newton's Law of Gravitation, a mass $M$ at the origin pulls a mass $m$ at position $\vec{r} = \langle x, y, z \rangle$ with a force $\vec{F}$.

- The magnitude of the force is $|\vec{F}| = \frac{GmM}{|\vec{r}|^2}$ (an inverse-square law).

- The direction is toward the origin, which is the direction of the vector $-\vec{r}$. A unit vector in that direction is $-\frac{\vec{r}}{|\vec{r}|}$.

The Vector Field: Combining these gives the gravitational field: $$\vec{F}(\vec{r}) = \left( \frac{GmM}{|\vec{r}|^2} \right) \left( -\frac{\vec{r}}{|\vec{r}|} \right) = - \frac{GmM}{|\vec{r}|^3} \vec{r}$$

Since $\vec{r} = \langle x,y,z \rangle$ and $|\vec{r}|^3 = (x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}$, we can write the components (letting $C = -GmM$):

$$P(x,y,z) = \frac{C \cdot x}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}}$$ $$Q(x,y,z) = \frac{C \cdot y}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}}$$ $$R(x,y,z) = \frac{C \cdot z}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}}$$

This is a 3D conservative vector field. The force of gravity is a gradient field! The potential function $f$ is what we call gravitational potential energy: $$f(x,y,z) = \frac{GmM}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}} = \frac{GmM}{|\vec{r}|}$$ (You can check by taking the gradient of $f$ that $\nabla f = \vec{F}$!)

Lecture Conclusion

What You Should Have Learned

- Vector fields assign vectors to points and are used to model flows and forces (like wind, water, or gravity).

- We visualize them in 2D and 3D by drawing a sample of vectors on a grid.

- A key type of field is a gradient field ($\vec{F} = \nabla f$).

- A vector field $\vec{F}$ that is a gradient field is called conservative.

- The scalar function $f$ is called the potential function.

- Gradient fields ($\nabla f$) are always orthogonal to their level curves/surfaces ($f=k$).

Where We Are Going

Now that we know what vector fields are, we are ready to do calculus with* them. In Lecture 16.2 Part B, we will learn how to compute the work done by a vector field on a particle moving along a curve. This will finally give meaning to the second type of line integral, $\int_C \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r}$.

Final Practice Set

Practice #1 (Sketching)

Problem: Describe and/or sketch the vector field $\vec{F}(x,y) = \langle 0, x \rangle$.

Let's test some points:

- Anywhere on the y-axis (where $x=0$), $\vec{F} = \langle 0, 0 \rangle$.

- At $(1,0)$, $\vec{F} = \langle 0, 1 \rangle$ (points up).

- At $(2,0)$, $\vec{F} = \langle 0, 2 \rangle$ (points up, but twice as long).

- At $(-1,0)$, $\vec{F} = \langle 0, -1 \rangle$ (points down).

This is a shear field. The vectors are all vertical. They are zero on the y-axis, point up for $x>0$, and point down for $x<0$. The magnitude increases as you move away from the y-axis.

Practice #2 (Find Gradient Field)

Problem: Find the gradient vector field of the 3D scalar function $f(x,y,z) = x \sin(yz)$.

- $f_x = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(x \sin(yz)) = \sin(yz)$

- $f_y = \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(x \sin(yz)) = x \cos(yz) \cdot z = xz\cos(yz)$

- $f_z = \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(x \sin(yz)) = x \cos(yz) \cdot y = xy\cos(yz)$

Answer: $\nabla f = \langle \sin(yz), xz\cos(yz), xy\cos(yz) \rangle$.

Practice #3 (Analyze 3D Field)

Problem: Analyze the 3D field $\vec{F}(x,y,z) = \langle x, y, 1 \rangle$. What does it look like?

- Analyze components: The 2D components are $\langle x, y \rangle$. This is the radial field from Example 3A, pointing directly away from the $z$-axis.

- Analyze z-component: The $z$-component is a constant $1$.

- Combine: At every point, the vector points "outward" from the z-axis and also "upward" with a constant push. This looks like a flow that is spreading out from a central line (the z-axis) while also moving uniformly "up."